Dr. Baldomero Roxas y Luz (1869–1965) was more than just an accomplished physician; he was a patriot, an educator, a writer, and a pioneering force in Philippine medicine. Known as the “Doctor of the Revolution,” he served the country during the struggle for independence and later devoted his life to obstetrics and gynecology.

P. Reyes y ca., editores. (1908). Filipinas: Imp. y litografía “Germania”.

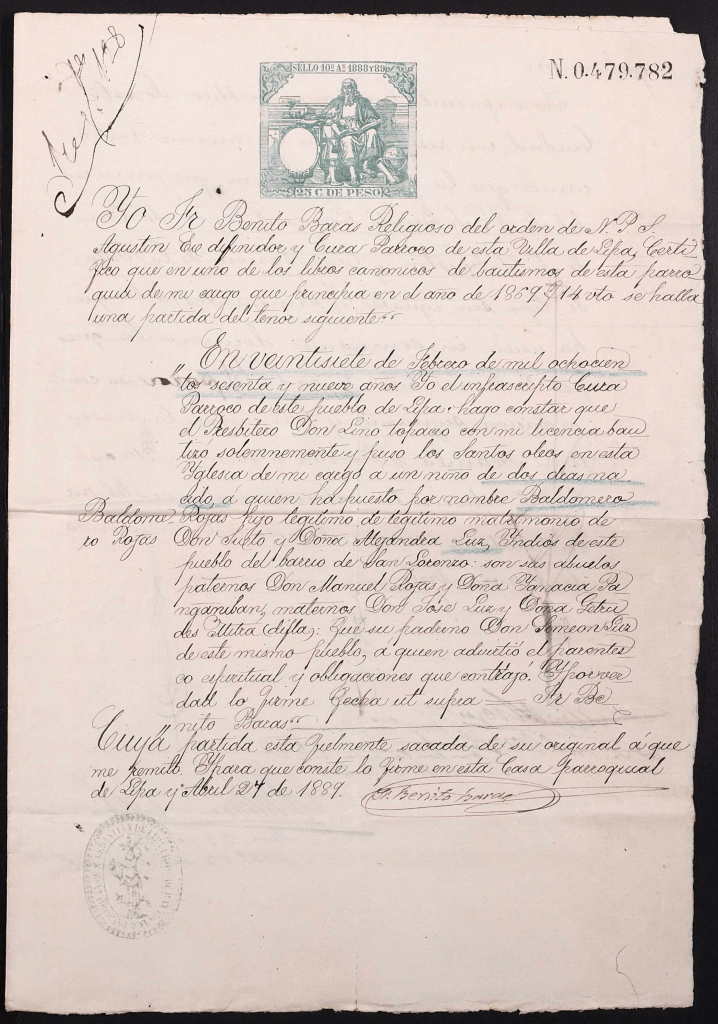

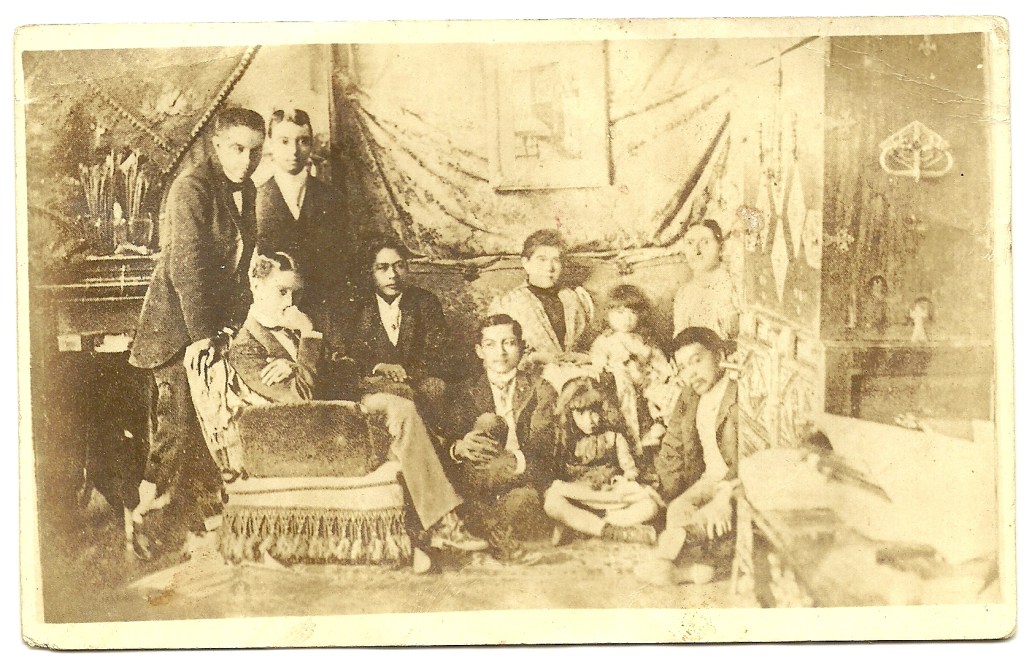

He was born on February 26, 1869, in Lipa, Batangas, the fifth of eighteen children in a well-respected and affluent family. His father, Don Sixto Roxas y Panganiban, was a prominent coffee planter and served as gobernadorcillo of Lipa from 1866 to 1867. His mother, Doña Alejandra Luz y Mitra, was a devout Catholic lay leader. Both parents were known for executive ability, piety, and steadfast dedication to the faith. They served as Presidents of the local chapter of the Apostolado de la Oración in Lipa, a religious association promoting devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The household into which Baldomero was born combined material prosperity with disciplined spiritual practice and civic responsibility.

His childhood coincided with the height of Lipa’s prosperity. The coffee boom had transformed the town into one of the wealthiest communities in the archipelago, and its leading families invested heavily in education and refinement. Baldomero received his early schooling at Lipa’s Escuela Pia before being sent to Manila to complete his bachillerato at the Ateneo Municipal. It was there, at the age of ten, that he first met José Rizal. Upon joining the school’s Congregación Mariana, his certificate of membership was signed by the organization’s secretary, Rizal himself. What might have seemed a routine administrative act would later assume symbolic significance, linking the young Batangueño student to the figure who would profoundly shape his political and moral outlook.

He received his Bachiller en Artes in 1885, graduating as sobresaliente, and later took medicine at the Universidad de Santo Tomás. Even during these early years, he displayed both intellectual seriousness and practical resolve. A dramatic episode in 1887 revealed his composure under pressure and left a lasting mark on his professional direction. When his mother went into difficult labor during the birth of his younger brother, Manuel, Baldomero was present. The newborn was delivered without breath, his nose obstructed by clotted blood. Acting swiftly, Baldomero cleared the obstruction by sucking the clots from the infant’s nose, enabling him to breathe and survive. Years later, Manuel would write in his Reminiscences that he owed his life to his brother, recalling that this was the first decisive intervention Baldomero made on his behalf. The incident exposed the perils of childbirth in an era of limited obstetric care and impressed upon the young medical student the urgency of improving maternal and infant health.

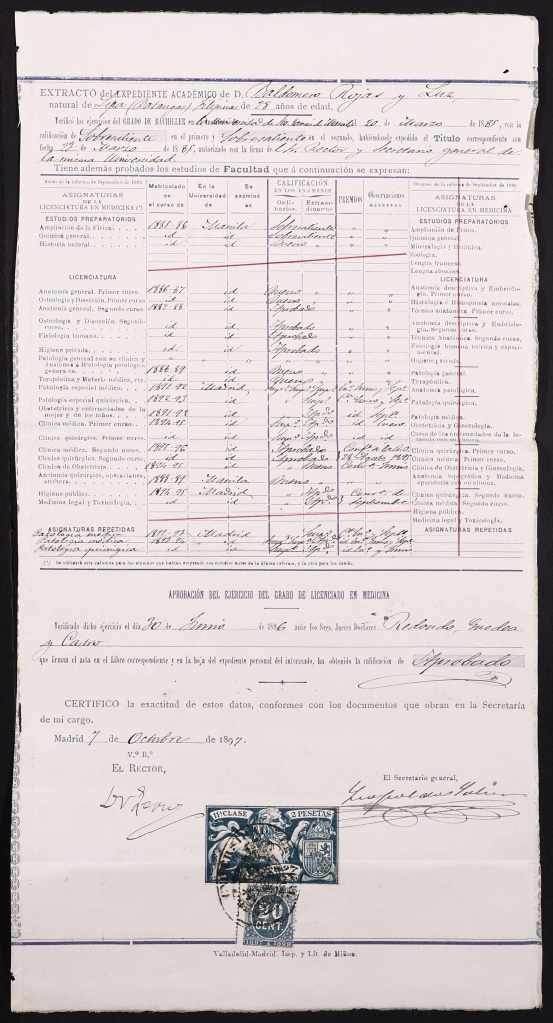

In 1889, his parents sent him to Spain to complete his medical studies at the Universidad Central de Madrid. Shortly after his arrival, however, calamity struck the family’s fortunes. Between 1889 and 1892, the coffee plantations of Batangas were devastated by a blight that erased accumulated wealth with startling speed. The Roxas family experienced some business reverses, and Baldomero found himself in Europe with diminished support. Rather than abandoning his studies, he worked to sustain himself, extending his course but strengthening his character. The experience hardened his discipline and dispelled any illusion of entitlement. In 1897, after years of perseverance, he earned his medical degree.

While in Madrid and Paris, Roxas became a central figure in the Filipino circle. He was among the seven original members of the Indios Bravos, a select group organized by José Rizal to reclaim the term “Indio,” long used as a racial slur, and to transform it into a badge of excellence. Alongside Juan Luna, Antonio Luna, Valentin Ventura, Gregorio Aguilera, and others, he committed himself to intellectual distinction and physical training, determined to demonstrate Filipino capacity in every field. The group’s camaraderie extended beyond symbolism; it fostered discipline, mutual encouragement, and a shared vision of national dignity.

Roxas later provided vivid recollections of Rizal’s habits and character. He remembered evenings in Juan Luna’s studio in Paris, where discussions ranged from literature to politics, and where Rizal urged younger compatriots to cultivate both mind and body. One story that highlights Rizal’s discipline occurred during a lively gathering in Paris. Despite earnest requests for him to stay longer, Rizal excused himself precisely at ten in the evening to honor his commitment to finish a chapter of his manuscript. For Roxas, this was not merely a matter of being punctual; it was a reflection of Rizal’s unwavering determination. Additionally, Roxas assisted Rizal with practical matters, such as handling correspondence related to his medical credentials and the circulation of “Noli Me Tangere,” which demonstrated the strong trust that existed between them.

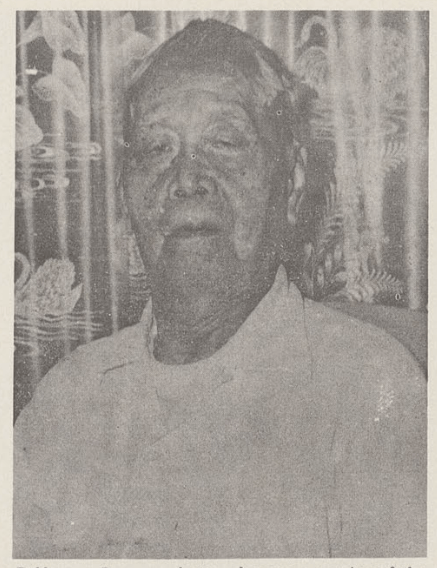

( Photo from the Teodoro Malabanan Katigbak Collection)

Despite having the opportunity to establish his medical career in Europe, Dr. Roxas returned to the Philippines in 1898, knowing full well that his homeland was embroiled in the second phase of the Philippine Revolution. On his return to the Islands, he met in Hong Kong many Filipino leaders who advised him not to continue his journey home, on account of the persecutions of Filipinos by the Spanish authorities. Undaunted and undismayed, Dr. Roxas continued his voyage as planned. He joined the Philippine Revolution against Spain. Here, he served as the Medical Staff of the Philippine Revolutionary Army as Chief Surgeon and Head of the Military Hospital of Lipa under the Southern Luzon Division Campaign of General Miguel Malvar. In Lipa and Taguig, he established and supervised military hospitals, often operating under precarious conditions and with scarce supplies. His dedication to wounded soldiers, irrespective of rank, earned him the title Doctor de la Revolución. His responsibilities extended beyond attending to the sick and wounded. Owing to his social standing and reputation for integrity, he was entrusted with diplomatic tasks, including negotiating the surrender of the Spanish forces in the Siege of Tayabas in August 1898, representing the Filipino revolutionary army.

Even amid conflict, he did not relinquish the pen. Together with his cousin Gregorio Aguilera Solís, he wrote for Columnas Volantes de la Federación Malaya under the pseudonyms “Lumiere Rouge” and “Dr. Pangloss.” His articles combined elegance and irony with political foresight. In Clarividencias: Sueños de Una Tarde de Primavera (Eng. Clairvoyance: Dreams of an Afternoon in Spring), he imagined a future Manila of towering steel structures and immense ships, industrial and modern, yet shadowed by the danger that Filipinos might become strangers in their own land under the American occupation. He concluded with a call for unity, insisting that redemption depended on collective resolve.

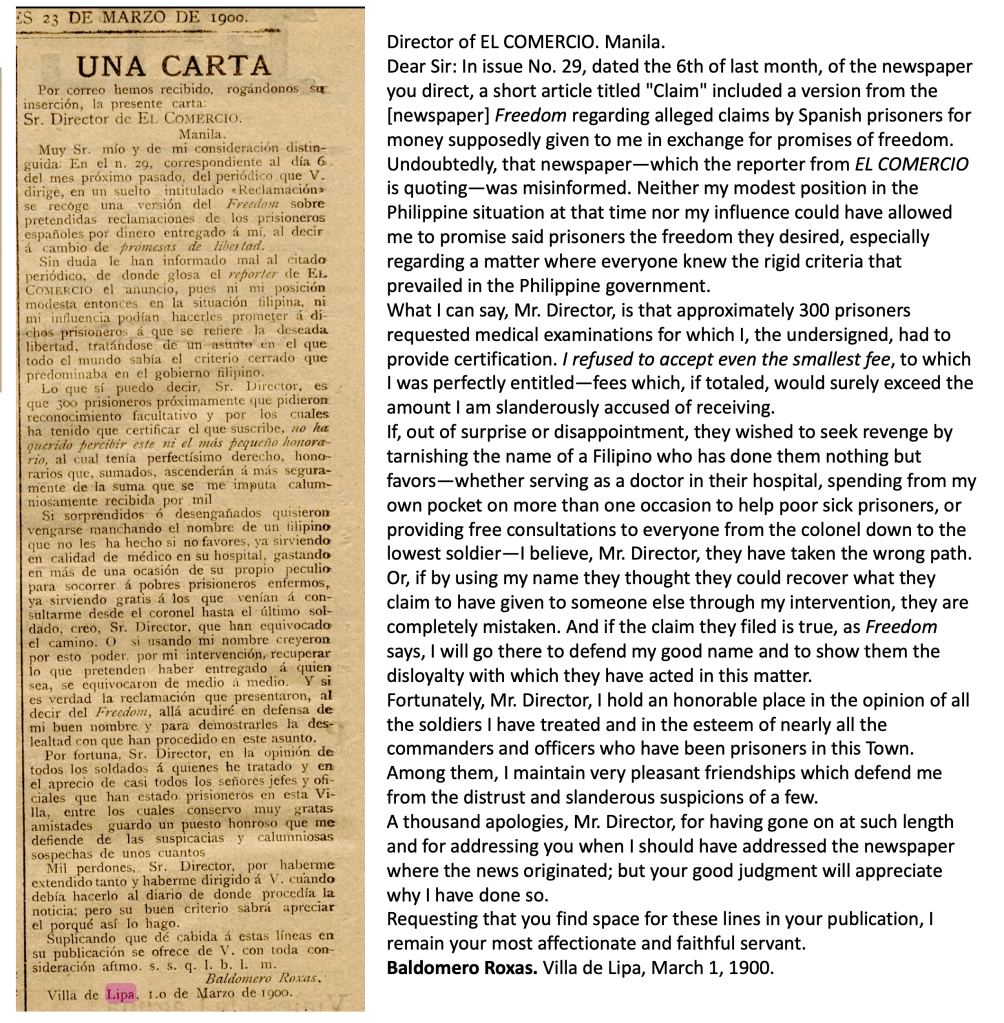

In March 1900, Roxas confronted slanders published in an American-run newspaper and reprinted in Manila, alleging that he had taken money from Spanish prisoners in exchange for promises of release. Writing from Lipa, he issued a firm rebuttal. He stated that he had provided medical certifications for hundreds of prisoners without accepting payment, though he was entitled to fees, and had even used his own funds to supply medicine and food. He emphasized that his oath as a physician compelled him to treat all men—from colonel to private—without discrimination. His response safeguarded his reputation and underscored his ethical consistency.

(Biblioteca Nacional de España/ Hemeroteca Digital)

With the establishment of the American government, Roxas turned from battlefield service to institutional development. The memory of his mother’s perilous delivery, and of the fragile life he had helped save, drew him decisively toward Obstetrics and Gynecology. In 1907, he became one of the pioneering professors of the Philippine Medical School, later the University of the Philippines College of Medicine. For thirty-four years, he taught and shaped generations of Filipino physicians. He served for two decades as head of Obstetrics at both the college and the Philippine General Hospital, setting standards of clinical rigor and professional conduct. He was a charter member of the National Research Council and later served as President of the Philippine Medical Association and the Philippine College of Surgeons.

Dr. Roxas married Pilar Asunción, the granddaughter of renowned Filipino portraitist Justiniano Asunción, in 1910. They had two children, Vicente Roxas and Pacita Roxas-Singson. Even in his later years, he remained active in his profession, continuing to practice medicine. His dedication to the field was unparalleled, making him the last among the pioneer Filipino doctors trained under the Spanish regime to retire from active practice. In 1959, he celebrated his 90th birthday, still hale and hearty. Known for his sharp memory, firm handshake, and steady hands, he continued to serve as a consultant for various hospitals. He maintained an active lifestyle, attending daily Mass and engaging with relatives, friends, and colleagues until his passing on September 9, 1965, at the age of 96.

References:

Aquino, José Arriola. “Baldomero Roxas, Rizal Friend, Is 90.” n.d.

Dirección General de Enseñanza Universitaria. “Expediente académico de Baldomero Rojas y Luz.” Madrid, Spain. Archival Reference Number: 31-16616-01294-00032. Digital images, FamilySearch. Accessed January 31, 2026. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-M73H-73H8.

Estado General del Apostolado de la Oración en Filipinas. Manila: Tip. de Santos y Bernal, 1911.

Festin, Mario R. “The Triumph of Science over Death.” Baldomero Roxas Memorial Lecture, 2017.

Galang, Zoilo M., ed. “Roxas, Baldomero.” In Builders of the New Philippines. Vol. 9 of Encyclopedia of the Philippines. Manila: Philippine Education Company, 1936.

Macapinlac, Ruben P. “Intimate Moments with Rizal in Paris.” The Sunday Tribune Magazine, n.d.

Roxas, Baldomero. “Una Carta.” El Comercio (Manila), 23 de marzo de 1900.

Santiago, Luciano P. “Dr. Baldomero Roxas y Luz” in Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. Philippines: University of San Carlos, 1994.

Solis, Max Bernard. “‘LUMIERE ROUGE’ o ‘DR. PANGLOSS’.” In Columnas Volantes de la Federación Malaya: Contribución a la historia del periodismo. [unpublished manuscript], 1927.