Don Gregorio Aguilera Solís was born in Lipa, Batangas, on November 1, 1869, entering the world just as the province was in the height of being a coffee producing center.

His father, Don Gregorio Aguilera Esguerra, was the son of a Spaniard, Don Juan Gabino Aguilera, and Doña Prudencia Amada Esguerra, a Filipina. Originally a resident of Singalong, Manila, the elder Aguilera arrived in Lipa in 1858 to serve as a public works inspector during the term of Gobernadorcillo Don Mateo Katigbak. He eventually made Lipa his permanent home, cementing his status within the local aristocracy through his 1860 marriage to Maria Solís, a daughter of the influential coffee baron Don Celestino Solís.

From this first union, Gregorio was born, along with his sister, Soledad. After Maria’s death in 1877, the elder Gregorio remarried in 1880 to her half-sister, Catalina Solís. This second marriage expanded the family, providing Gregorio with three half-siblings: Vicenta, Remedios, and Luis.

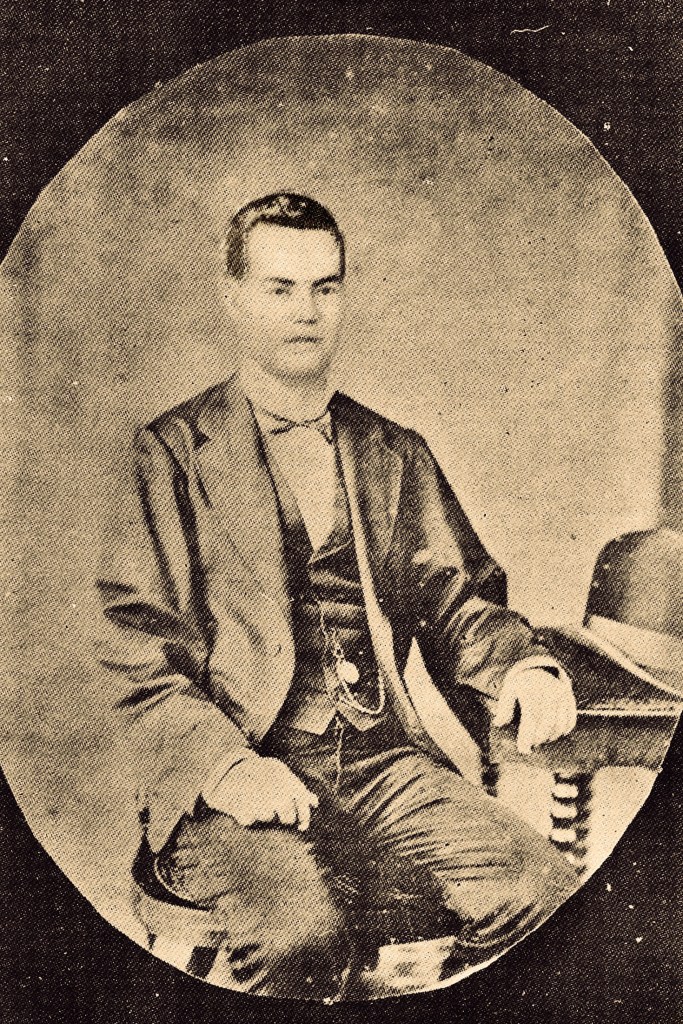

Though of partial Spanish descent, Gregorio’s features were distinctly Filipino. He had a round face, prominent eyes, and a flat nose. In youth he was slender, though slightly stooped by a small hump at the back of his neck—a trait shared by members of the Aguilera family. Later in life, after his years abroad, he would return to Lipa with a fuller figure, more imposing but never elegant. In Batangas he was known simply as “Goring,” and later, with affection and respect, as “Mamang Goring.”

from the book “Few There Were (like my Father)” written by Maria Kalaw-Katigbak

He was educated at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila, where he earned the Bachiller en Artes in 1889. As a student he distinguished himself for intelligence and literary promise. His academic excellence was unquestioned—until his final year, when his Jesuit teachers discovered a clandestine poem beginning with the incendiary line: “Muera la madrasta España…” (Death to stepmother Spain).…” The medal for excellence was withdrawn. That he suffered no harsher penalty during such politically charged years remains remarkable.

For a time, he contemplated entering the Jesuit order. He even kept a notebook in which he recorded his faults and moral struggles in an effort at self-discipline.

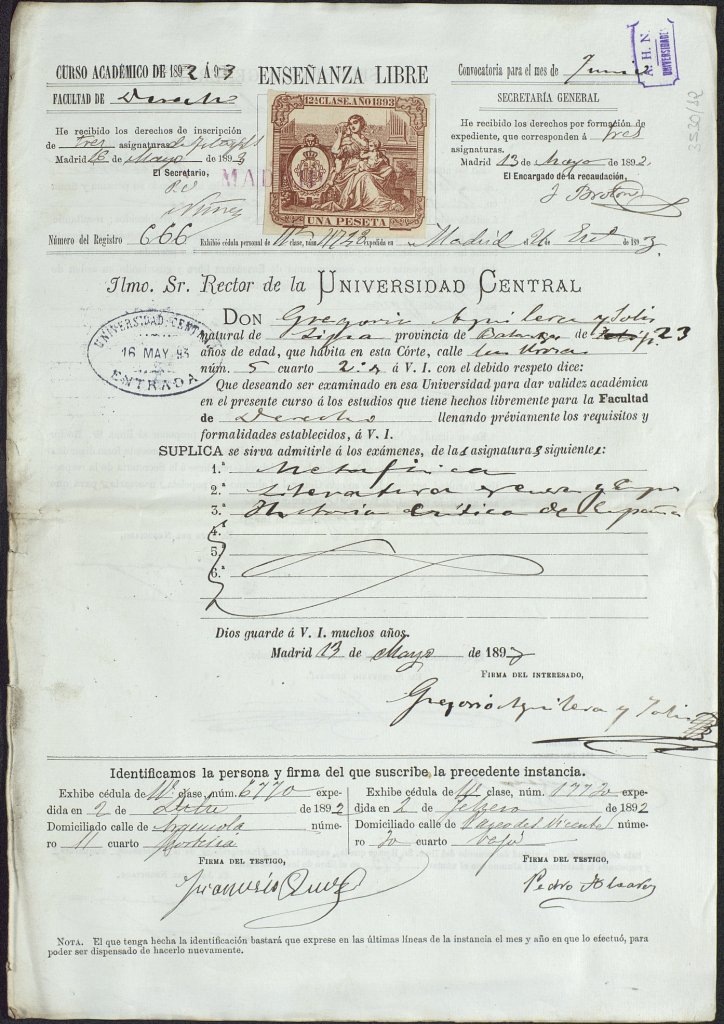

He then traveled to Spain to further his studies at the Universidad Central de Madrid, initially intending to take religious vows however, Europe changed him. His stay in Paris and Madrid erased his initial priestly vocation. He embraced a bohemian life in Madrid. He began several university courses but completed none. Still, even amid personal excess and romantic entanglements, his concern for the fate of his homeland never left him

Source: Archivo Histórico Nacional (España), UNIVERSIDADES,3530,EXP.12_005

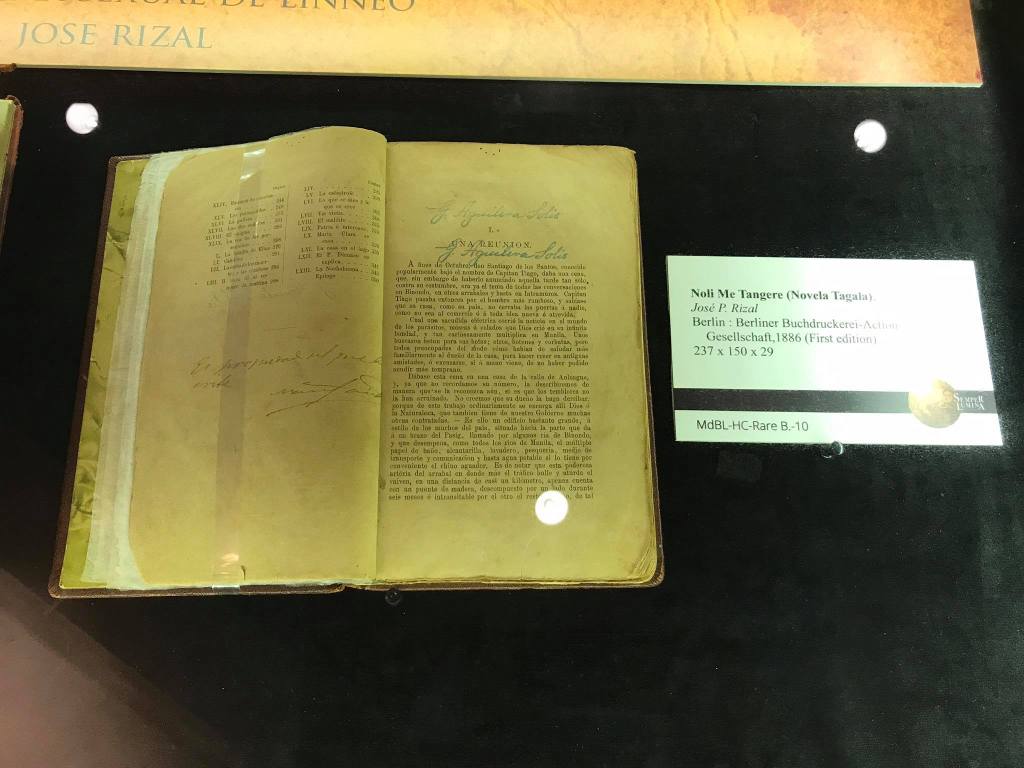

He joined the Filipino expatriate community that agitated for reforms and greater autonomy for the Philippines. General José Alejandrino later recalled that Dr. José Rizal regarded Aguilera as one of the finest minds among the Filipino students in Spain. Aguilera became a member of the Asociación Hispano-Filipina and served on its governing board. He signed the December 21, 1892 petition to Spain’s Overseas Minister requesting the acceptance of 7,500 pesetas to place Félix Resurrección Hidalgo’s painting Aqueronte in Madrid’s Retiro Park. He also signed the protest submitted to the same ministry regarding the infamous events in Calamba under General Weyler. During these four years, he traveled widely across Europe, acquiring both culture and cosmopolitan polish.

Aguilera returned to the Philippines at the height of a revolution that gave way to the First Philippine Republic. During this period, he was appointed Director of the Instituto Rizal in Lipa and named representative of Batangas to the Malolos Congress. The Institute, inaugurated on January 2, 1899, offered a modern civic-military curriculum that combined classical studies with agronomy, commerce, mechanics, languages, gymnastics, music, drawing, and even military instruction. It aimed to form young men devoted not to private ambition but to the service of the nation.

On January 15, 1899, Aguilera signed the Institute’s circular as President. Its language reveals his philosophy: education must awaken civic conscience, cultivate intellectual superiority, strengthen the body, refine the arts, and above all instill an unwavering conviction in the Filipino nation’s right to integrity and independence. The school was short-lived, as brief as the First Philippine Republic itself, but it left a clear imprint of nationalist purpose.

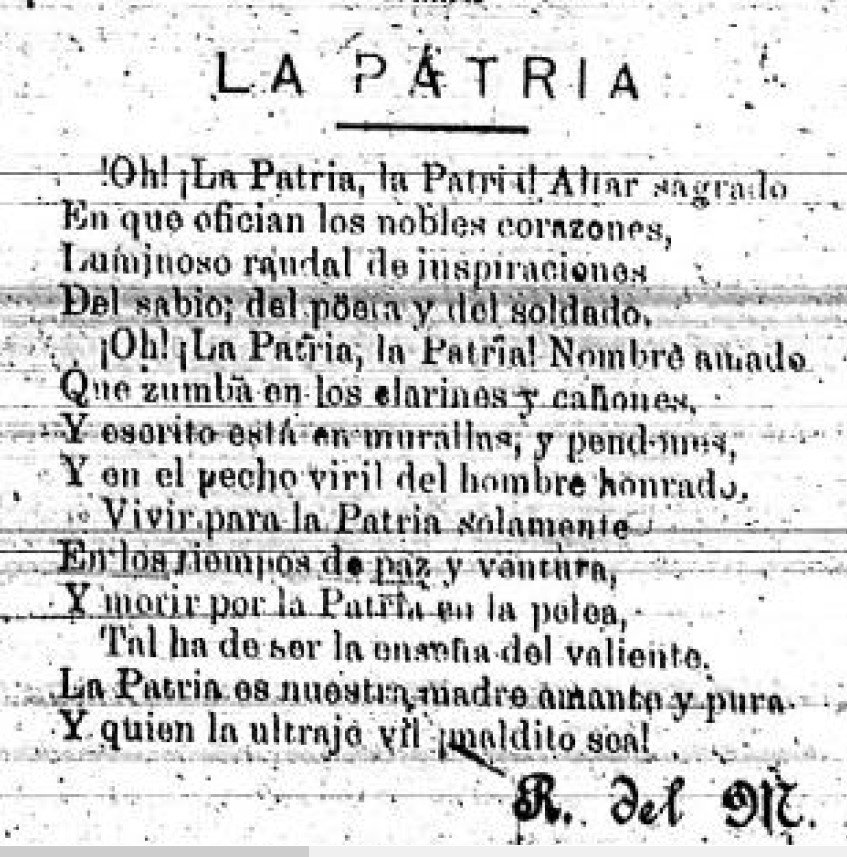

On April 11, 1899, he founded Columnas Volantes de la Federación Malaya, the first newspaper established in Batangas. Though technically not listed as editor, he was widely recognized as its guiding force—the “soul” of the weekly. The paper became an invaluable chronicle of events in southern Luzon during the revolutionary struggle.

In this publication, Aguilera preferred influence without display. He often wrote under the pseudonym “R. del M.,” whose meaning sparked speculation. The poems signed with those initials ranged from ardent love lyrics to patriotic sonnets such as La Patria, which called for living and dying in service of the country. His verse revealed both romantic excess and fervent nationalism.

His home became a gathering place for farmers, landowners, students, laborers, and idle youth alike. He subscribed to newspapers from Manila, Europe, and the Americas. He dispensed cigars generously from his library window; even street sweepers lingered in hope of a “Londres” cigar. This easy hospitality, extended to all without distinction, earned him enduring affection.

He dressed simply, often carelessly, favoring loose white suits. When necessary, he wore a conspicuous solitaire ring and diamond-set gold chain, joking that without them no one would consider him respectable. He understood appearances and human vanity well enough to manipulate both.

Aguilera’s political career bridged two sovereignties. During the Republic, he represented Batangas in the Malolos Congress alongside Mariano López. Under the American occupation, he became Municipal President of Lipa in 1902 and, two years later, Provincial Governor of Batangas. His election was decisive; his popularity required no campaign.

When William Howard Taft toured the archipelago promoting pacification and the Federal Party, Aguilera chaired the local committee in Lipa. Yet his position during the early American occupation was fraught. He believed continued armed resistance futile but refused to betray compatriots. He helped persuade certain revolutionary leaders to surrender diplomatically. Nevertheless, when American authorities intensified repression under the Bandolerismo Law—detaining prominent citizens and forcing them to guide troops—Aguilera himself was arrested.

During one grueling forced march to Balete, an American officer mocked him: “Tired, aren’t you?” Aguilera gestured toward the burning town and replied that he was merely watching the Statue of Liberty illuminate the world. On another occasion he offered himself in exchange for the release of fellow prisoners, declaring that bravery is easily claimed by those who carry arms.

As governor, he was humane to a fault. He avoided the sight of prisoners at the provincial jail, yet regularly sent them food and cigars at his own expense. He left office with diminished means. His administrative record was modest; he governed as a man of letters more than as an executive. Part of his personal library was even transferred to the provincial capital so he could remain among his books. Evenings were spent in conversation with poets such as Jesús Balmori. Governance, for him, was inseparable from reflection.

Aguilera was admired for affability, education, and generosity. He once dismissed a former servant who addressed him as “Governor” instead of “Mamang Goring,” yet forgave the man’s debt before letting him go. He moved easily among aristocrats and commoners alike. His democratic instinct was genuine, though tempered by paradox. He possessed bold ideas but seldom sought the spotlight. He inspired institutions but often left their practical burdens to others.

He died at the age of fifty-one on January 16, 1921, leaving no vast fortune and no monumental public works to bear his name. What he left instead was influence: a generation stirred by nationalist education, a newspaper that preserved the memory of revolution in Batangas, and a reputation for intellectual brilliance coupled with human warmth.

Gregorio Aguilera Solís was, in essence, a poet in public life. He loved liberty, beauty, conversation, and country—sometimes in that order, often all at once. His flaws were visible; so too were his virtues. In him, the cultivated mind of Europe met the fervent heart of a Filipino patriot, and for a brief, turbulent period in Philippine history, that union shaped the spirit of Batangas.

(Photo by Mak de Castro)

References:

Solis, Maximo Bernardo A. El Alma del Semanario. Columnas Volantes de la Federación Malaya: Contribución a la Historia del Periodismo Filipino. Balmaceda Collection. National Library of the Philippines. 1927.

Artigas y Cuerva, Manuel. Galeria de filipinos ilustres Manila: Imp. Casa Editora “Renacimiento”, 1917-1918.